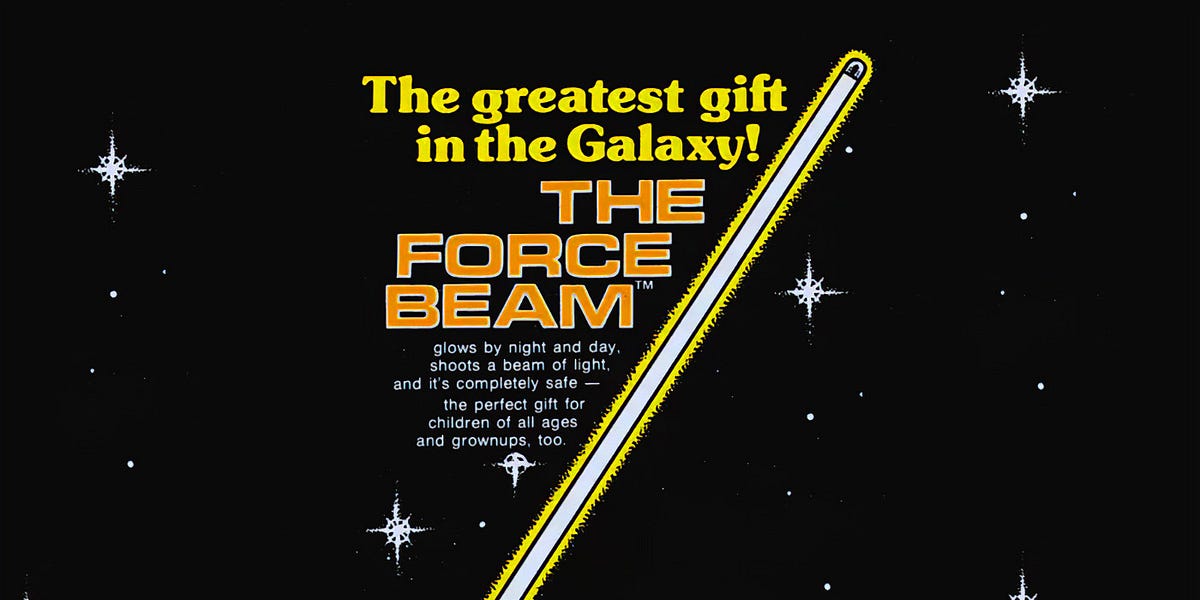

I still remember when my sister spotted the Force Beam toy in a newspaper ad right around the time Star Wars first came out. She held the paper up and showed me, pointing at the photo with a smile because she knew how much I was obsessed with the movie. The ad made it look like the closest thing you could have to a real lightsaber. While the ad was black & white, it still appeared to glowing and dramatic in a way that seemed almost magical to me then. From that moment the image stuck in my head, and I kept going back to it again and again, staring at the paper and imagining what it would feel like to hold one, to actually hold a lightsaber. As Christmas drew closer, I quietly held onto the hope that it would show up under the tree, thinking that if I was lucky enough to get it, there would be no better gift in the world.

But why a Force Beam and not an official Star Wars toy? When Star Wars exploded in May 1977, there was no merchandise ready to meet the sudden demand. Kenner, which had just secured the toy license, had only a few months to design, tool, and produce action figures and other toys. That timeline was impossible to meet before Christmas, since creating molds, setting up production lines, and shipping toys from overseas factories usually took close to a year. Instead of figures and lightsabers on shelves, Kenner offered the famous “Early Bird Certificate Package,” which let parents buy a cardboard stand and a mail-in promise that figures would arrive in 1978. This gap between demand and supply is what gave bootleg and knockoff toys like the Force Beam a chance to appear during the 1977 holiday season, filling shelves while the official products were still months away.

That Christmas morning came and went without a Force Beam waiting for me, and at first I felt the sharp sting of disappointment. Other kids were a lot luckier. But the toy never left my mind, and in a strange way not having it made me more interested in it. I kept saving ads when I saw them, seeing if my friends had gotten one, and studying every detail I could find about how it worked. Over time, it turned from just a toy I wanted into something bigger, a piece of Star Wars history that fascinated me. In fact, some of my earliest eBay searches were for trying to track down a Force Beam of my own (at a reasonable price). Sadly, it never happened.

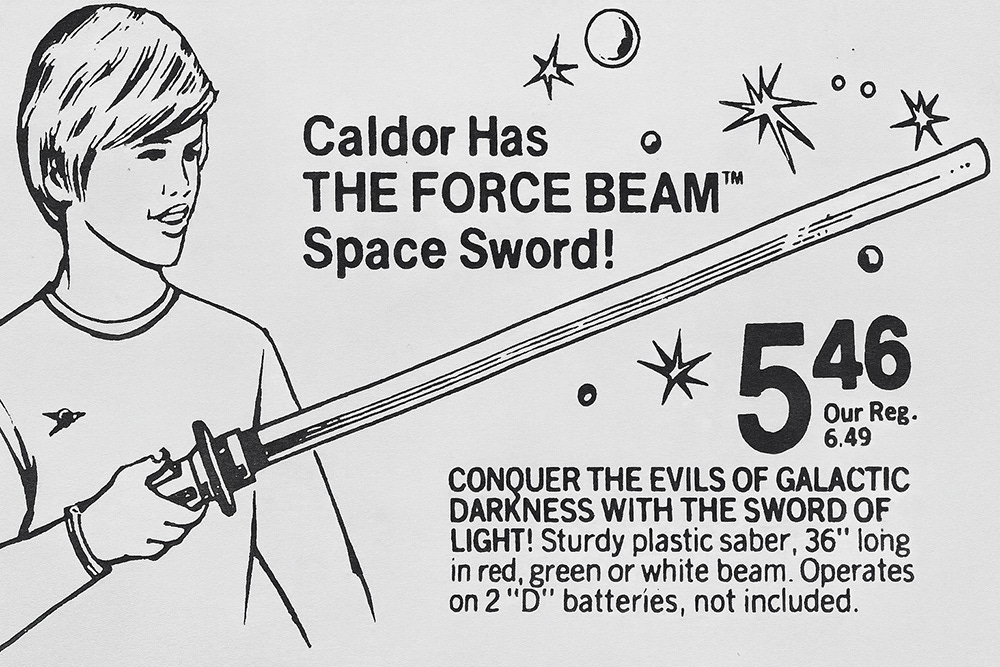

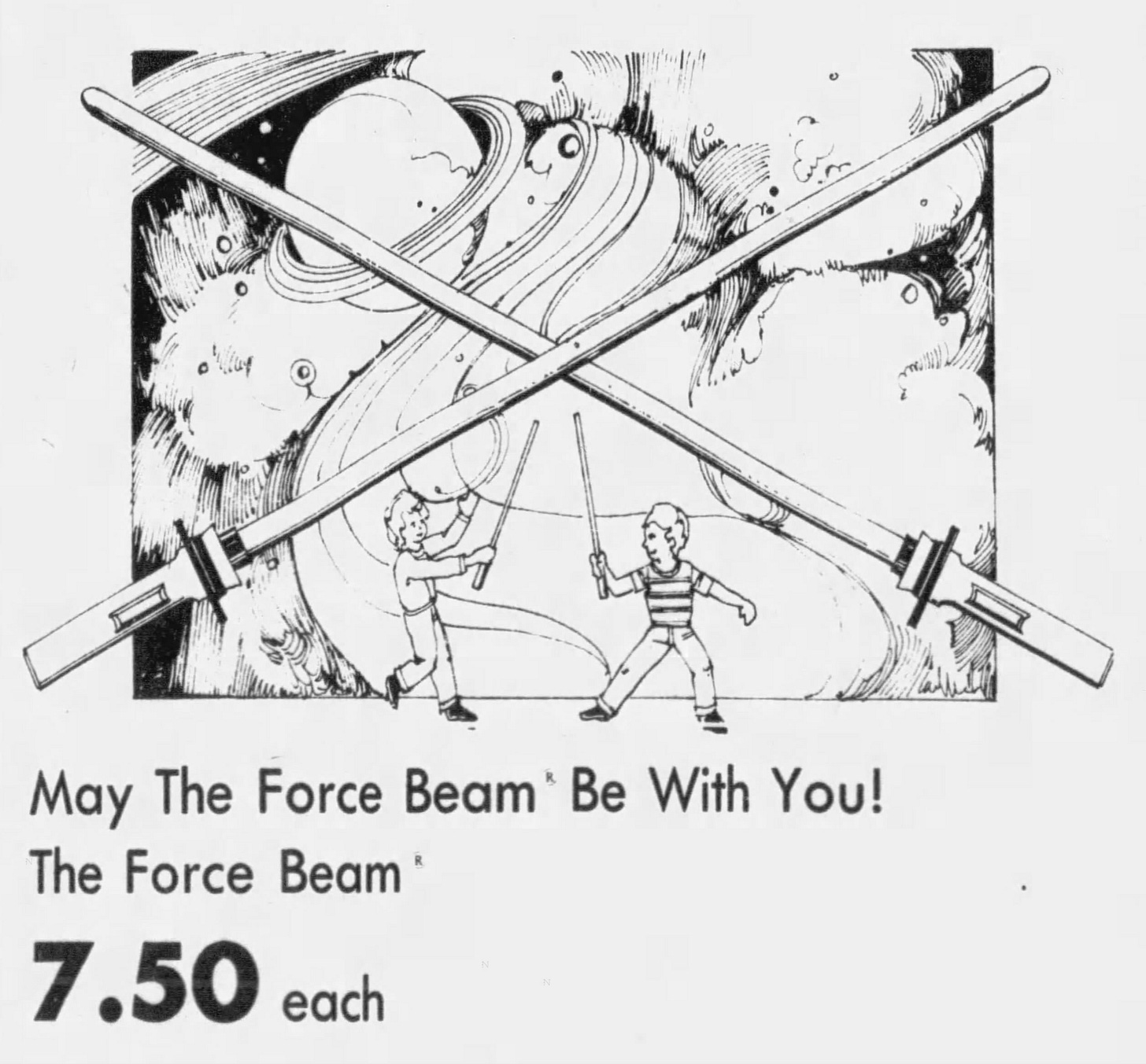

Before I talk about why this unlicensed bit of Star Wars magic existed, let me explain what the Force Beam was and how it worked. The Force Beam was a simple battery powered toy built around a flashlight style handle with a colored plastic filter and a long translucent tube attached at the end. When you switched it on, the bulb in the handle shone light through the hollow tube, giving the effect of a glowing blade. The tube came in red, white or green and stretched to about three and a half feet, making it long enough to swing like a sword but also flimsy enough that it bent or cracked with rough play. The whole build was light and inexpensive, more of a novelty than a sturdy weapon, but in a dark room it produced just enough glow to pass as a lightsaber stand-in.

While I never acquired a Force Beam, I have tried to figure out exactly where it and some its variants came from, here is what I have figured out about a few of them. In the U.S., the Force Beam appeared by Christmas 1977, distributed by Jack A. Levin & Co. of New York. These toys were sold at department stores, through comic ads and at novelty outlets. Memorable because they were packaged as an unlicensed glowing sword at a time when no official lightsaber yet existed. Surviving examples list Levin as distributor but carry no “Made in U.S.A.” stamp or Durham branding, which leaves their actual origin uncertain. Collectors often assume they were imported, since Levin was known as a distributor rather than a manufacturer, but no factory source has been confirmed.

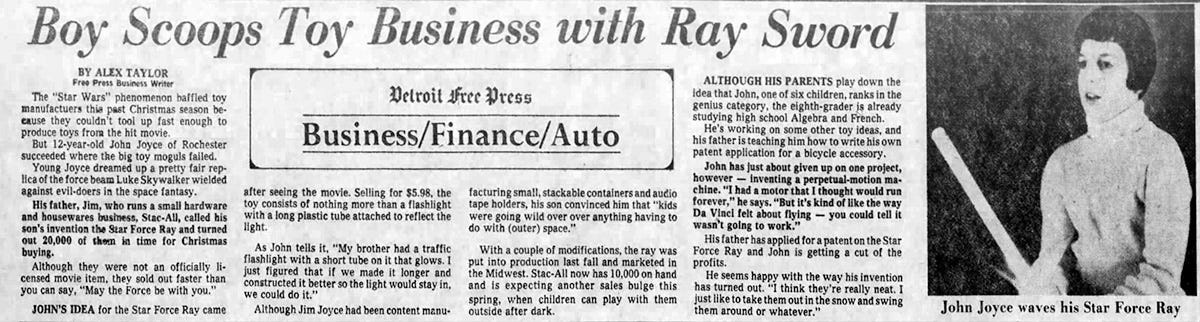

At the same time, American kids could also find very similar toys from other quick-moving companies. One called the Star Beam, made domestically by Durham Industries, Inc. in New York and marked “Made in U.S.A.” in 1977. But these were just the tip of the of fake lightsaber iceberg. Prepare to be inspired by John Joyce, a 12 year old, who with his father managed to get 20,000 of his Star Force Rays on shelves by Christmas.

Taken together, the evidence shows that American shelves carried at least one confirmed homegrown saber toy and another nearly identical line with unclear but probably overseas origins. This doesn’t really cover it though, since lots of different companies were out there making light up swords under different names.

But that was just in the US, in Britain, the toy reached children through Loydale Limited of Wokingham. Beginning in 1978, Star Wars Weekly famously carried full page mail order ads offering a 41 inch illuminated Force Beam for £2.95 plus postage. The ads leaned heavily on Star Wars imagery, even showing Luke and Leia lookalikes in early versions, before shifting to more generic artwork after what seems to have been legal pressure. Like the Levin distributed U.S. examples, these UK Force Beams do not carry any “Made in” marks or Durham branding. All that can be confirmed is that Loydale acted as the seller and promoter, which makes it likely but not proven that the UK stock came from the same supply chain Levin was using in the States.

What we can say with confidence is that not all of these toys came from one source. The Durham Star Beam is documented as U.S. made. The Levin and Loydale Force Beams, however, lack country of origin markings, leaving their true manufacturing base unknown. They may have been produced in Asia or Europe and funneled through different distributors, but so far no packaging or records have surfaced to prove it. A trade advertisement claimed that more than 250,000 units had been sold in Britain and called the Force Beam the fastest selling science fiction action toy in the country, though no audited figures support that number. For the United States no sales totals are known, only that the toys were available in time for Christmas 1977 and circulated widely enough to be well-remembered.

I am not sure exactly how, but the Force Beam managed to exist without a visible court case. This seems surprising given how closely it mimicked Star Wars imagery. Timing probably played a big part as to why not. The toy reached the market in late 1977 and early 1978, before Kenner had its own lightsaber ready and before Lucasfilm had a strong licensing enforcement structure in place. The makers avoided using the trademarked word “lightsaber,” calling their toy the Force Beam instead. That left less direct grounds for an infringement case. The companies involved were also small and quick moving. Jack A. Levin & Co. in the United States was a distributor rather than a major toy maker, and Loydale Limited in the United Kingdom was a mail order firm that could vanish easily if challenged.

There are signs of pressure, even if no public lawsuit followed. As I mentioned, those U.K. ads used art that looked almost identical to Luke and Leia. Later versions dropped those characters in favor of more generic figures. That change suggests Marvel UK or Lucasfilm objected behind the scenes, and the ad was toned down to avoid further trouble. Collectors generally read this as the likely result of cease and desist letters rather than formal litigation.

Lucasfilm did pursue other cases once its licensing office was better established. In later years it sued over “Light Saber” medical devices, replica sabers, and even a laser pointer marketed as a lightsaber. Those cases prove that the company was willing to defend its marks aggressively. The absence of a Force Beam lawsuit most likely reflects its short lifespan, small distribution network, and the speed with which official Kenner products hit shelves.

Looking back, it is almost fitting that I never unwrapped a Force Beam on Christmas morning. The toy itself was fragile, a quick cash-in that faded as soon as the official lightsabers arrived, but the mystery around it has lasted far longer than its plastic tube ever could. Not getting one kept the idea alive in my head, and years later I still find myself chasing down old ads, collector photos, and scraps of information about how it was sold in the U.S. and the U.K. The Force Beam may have been a stopgap toy, but for me it has become another symbol of that first wave of Star Wars mania, when kids wanted anything that felt like a lightsaber and the market rushed to fill the gap that Kenner couldn’t yet fill.

While working on this post, I started playing around various old ads and thought with some work, one of them would make a t-shirt that I would like to get. So I added it to the store, check it out, and grab your own Force Beam T-Shirt.

Trending Products

![NOW Country Classics: 90âs Dance Party[Lemon & Spring Green 2 LP]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61hVquUofcL._SL500_._SS300_.jpg)