During Halloween when I was a kid, the great thing you could get was a full-sized candy bar. Sure we loved getting our bags filled with smaller candy bars, but we took them for granted. When I would get home, I’d run up to my room to keep my candy safe from my sisters (or my mom), and pour it on the floor. Separating all the various candies into piles of perceived value, I never questioned where the smaller format candy bars came from or why they had become a staple around the Halloween season. It turns out, their history was pretty interesting.

The idea of selling smaller versions of candy bars didn’t start with Mars. Stores had been labeling smaller candy for decades under the “junior” label. Curtiss Candy Company, the maker of Baby Ruth and Butterfinger, started packaging and selling “Junior” size bars in the 1950s (even though the Junior label was around before that). These smaller bars gave them a way to reach new situations like school lunches and parties while keeping the candy familiar. They were wrapped individually, easy to pack and hand out, and recognizable as the same treats people already liked, just in smaller form. So, of course, they were already being sold in conjunction with Halloween.

Mars, the powerhouse candy company, entered the picture later. They saw all the protentional in a reduced size. In 1961 the company began offering its own “Junior” size bars, a portioned version of its regular products. Still, there is a problem with the name itself, junior implies smaller. So what if they came up with a name that suited a smaller candy, but didn’t just mean that you got less.

In April 1968 Mars replaced the “Junior” label with “Fun Size” and began rolling out the new format nationally on Milky Way, Snickers, and their other best-selling brands. The name made the small bars sound like something more than just smaller candy, and it caught on quickly.

Curtiss had been using “Junior” for years, but in August 1971 it began using the phrase “Fun Size” on its own Baby Ruth and Butterfinger bars. Mars viewed this as a threat to the identity of its new brand and took Curtiss to court in 1972. Others have written about the legal back-and-forth, like this Tedium article from 2018, but what interested me more was how this small idea changed how candy was made and sold. Still, let me discuss some of the basics I learned about these legal wranglings.

The company argued that people already connected “Fun Size” with Mars products and that Curtiss should be stopped from using it (even though Curtiss was using junior before Mars started using it). The court disagreed, saying Mars hadn’t yet built a strong enough link between the term and its candy. Curtiss was allowed to keep using the label while the case continued.

Mars went to federal court in 1974, this time going after Standard Brands, which had acquired Curtiss by then. The new suit focused on whether Mars could claim exclusive rights to “Fun Size” and whether others were infringing on that claim. Mars didn’t win immediate control, but the company stayed persistent. On October 19, 1976, it secured federal registration for the mark FUN SIZE (Reg. No. 1,050,880), giving it formal ownership of the term in the candy category.

The trademark, however, didn’t give Mars total control. Courts had already ruled that “Fun Size” was too descriptive for consumers to associate it only with one company. Mars couldn’t stop others from using it in a descriptive way, and later cases confirmed that point. Some competitors continued using the phrase openly, including Curtiss and its later owner, Nestlé, which kept selling “Fun Size” Baby Ruth and Butterfinger bars for decades. Other companies chose variations such as “Snack Size,” “Treat Size,” or “Miniatures,” which you have probably seen if you have bought any candy in the last 50 years.

So, by the end of the 1970s, small and individually wrapped bars had become a standard part of the candy aisle. “Fun Size” remained tied most strongly to Mars brands, but the phrase itself spread into common language and was no longer something any one company could own outright. It became a shorthand for miniature candy in general, a label that grew even more valuable as it became linked with Halloween. But store-bought candy didn’t always dominate the holiday. Before the late sixties and seventies, Halloween treats could be very different.

Before smaller sized bars took over, Halloween treats varied greatly. While junior bars or just smaller sized candies were available, a lot of families didn’t stockpile branded candy in advance. Many handed out homemade treats like popcorn balls, cookies, fudge, or candied apples. These were often made in large batches and wrapped loosely in wax paper or cellophane. In many neighborhoods, these homemade items were a point of pride, and kids knew which houses had the best popcorn balls or the biggest apples. When I was growing up, the majority of treats were pre-wrapped large brand candy, but houses with older people living there still gave out these treats.

Loose candy from bulk bins was also common. Stores sold caramels, hard candies, and candy corn by the pound, and families would portion them out into small paper bags or give them out by the handful at the door. A few of the best households bought full-size candy bars, but they were expensive to give to every child, so they tended to appear in smaller neighborhoods or from particularly generous homes. We marked these homes and would often try and return for multiple bars.

Some people gave out small toys or novelty items, like whistles, plastic rings, or even comics books. The mix varied by neighborhood or town, but you really never new what you were gonna get as a kid back then. The thing is, neighbors knew each other, and the idea of questioning the safety of what you received was not widespread. Halloween candy was not yet as standardized, and factory packaging played a much smaller role than it would just a decade later.

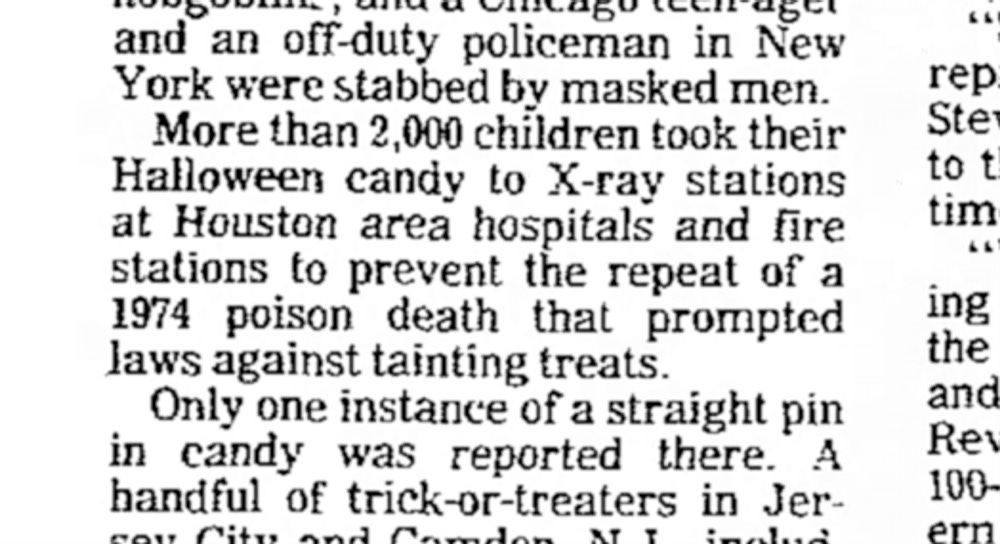

That familiar mix of homemade and bulk treats started to change more dramatically in the early 1970s and it wasn’t just because of the newly available smaller sized bars. A series of news reports about alleged tampering made national headlines, beginning in 1970 with a widely publicized case in New York and continuing through the decade. The most infamous incident came in 1974, when eight-year-old Timothy O’Bryan died after eating cyanide-laced candy on Halloween night in Texas. The case turned out to be a murder committed by his father, but at the time it was reported as a Halloween poisoning and became a defining story.

The coverage surrounding these cases created widespread anxiety about trick-or-treating. Parents were urged to check their children’s bags carefully. Some hospitals offered free X-rays of Halloween candy to look for foreign objects. PTAs, schools, and local police departments began advising families to discard anything homemade or loosely wrapped.

Candy companies responded quickly. Mars, Curtiss, and others began printing banners on their multipacks with phrases like “Individually Wrapped for Your Protection” and “Sealed for Safety.” Grocery store ads echoed the same language, positioning factory-wrapped candy as the responsible choice for Halloween. Within just a few years, individually wrapped branded candies went from being one option among many to the expected standard.

All of this happened even thought the reports of tampering turned out to be false. Police investigations frequently uncovered hoaxes, pranks, or accidents, such as children inserting objects into their own candy to scare siblings or parents mistaking harmless defects for tampering. Studies in the 1980s found no verified cases of random strangers killing or seriously injuring children with Halloween treats. The fear persisted, though, fueled by sensational news coverage and community warnings. Factory-sealed candy fit neatly into that atmosphere, offering parents a simple way to feel more secure. Homemade treats and bulk candy faded from most trick-or-treat bags, and factory packaging became the easy go-to thing to give out on Halloween night.

While safety is good, their might have been another motivation for these companies. Shrinking the bar was smart business. Mini versions used the same ingredients and often the same equipment as regular bars, so production costs stayed nearly the same, but the smaller portions could be sold at a higher price per ounce. That means stronger profit margins without much extra investment. Multipacks also simplified shipping and encouraged bulk purchases, whether or not is was Halloween. I buy bags of peanut putter cups all year long

When I first started thinking about these small candy bars scattered across my bedroom floor when I was a kid, they just seemed like a novelty, a smaller version of something I already knew. But behind that small wrapper was a much larger story. Simply shrinking the candy bar turned into a marketing success, a legal battle, and a reflection of changing habits around safety and convenience. Fun size bars didn’t just make candy smaller, they changed how it was sold, how it was shared, and how a holiday worked. These little bars don’t just fill trick or treat bags, they are an integral part of Halloween. Now if you will excuse me, I am going to eat way too many well-deserved fun size treats.

Trending Products

![NOW Country Classics: 90âs Dance Party[Lemon & Spring Green 2 LP]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61hVquUofcL._SL500_._SS300_.jpg)